As the back to school specials start popping up in shops, our thoughts turn to the novels in which the central characters begin their schooldays. The following excerpts from a paper Nancy and Stephanie presented at the sixth biennial meeting of the Society for the History of Childhood and Youth give a sense of those early schooldays.[1]

In our chosen books, the first days of school serve to introduce readers to the cast of characters they will come to know in these series of schoolgirl stories. Right from the start, readers learn about the character of the key figures in the stories, of those who will fit the schoolgirl mold and of those who will reinforce the principles of right and justice by their violation of them. The creation of these schoolgirl societies establishes the conventions of school life, revealing how these little commonwealths will be governed by their citizens and what role, whether large or small, adult authority will play in this governance. Girls’ awareness that they entering a community whose educational purpose went beyond the academic is reflected by our young heroines who ‘keep wondering what school will be like’.[2]

In one of the American novels, Marjorie Dean moves to a new town just before the start of her first year of high school. Before the school year begins, she undertakes a reconnaissance mission of her new school and ponders how she will fit into the already established group of girls. “She was not afraid to plunge into her new school life, but deep down in her heart she felt some little misgiving. What if the new girls proved to be neither likeable nor companionable? What if she liked them but they didn’t like her?”[3] Marjorie had observed a group of her new classmates before starting school and met them soon after she had registered for classes. On her first day of school, Marjorie is asked a question by Muriel Harding that will prove crucial to her finding a place among her classmates: “‘By the way, do you play basketball?’.”[4] Marjorie’s affirmative answer earns her invitation to the tryouts for the class team that will be held later in the week. While Marjorie meets with her new English teacher, who had conveniently been the best friend in college of Marjorie’s former teacher, Muriel sizes up Marjorie and delineates her attributes – fashion sense, class, athletic prowess, and social connections all work together to establish Marjorie’s place in her new school.

In one of the American novels, Marjorie Dean moves to a new town just before the start of her first year of high school. Before the school year begins, she undertakes a reconnaissance mission of her new school and ponders how she will fit into the already established group of girls. “She was not afraid to plunge into her new school life, but deep down in her heart she felt some little misgiving. What if the new girls proved to be neither likeable nor companionable? What if she liked them but they didn’t like her?”[3] Marjorie had observed a group of her new classmates before starting school and met them soon after she had registered for classes. On her first day of school, Marjorie is asked a question by Muriel Harding that will prove crucial to her finding a place among her classmates: “‘By the way, do you play basketball?’.”[4] Marjorie’s affirmative answer earns her invitation to the tryouts for the class team that will be held later in the week. While Marjorie meets with her new English teacher, who had conveniently been the best friend in college of Marjorie’s former teacher, Muriel sizes up Marjorie and delineates her attributes – fashion sense, class, athletic prowess, and social connections all work together to establish Marjorie’s place in her new school.

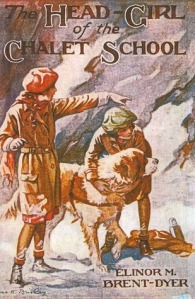

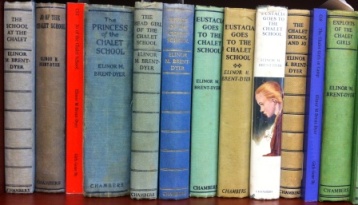

The first days depicted in Eleanor Brent-Dyer’s The School at the Chalet are not only the first days for new pupils, but also for the school itself. Madge Bettany founds the school and populates the student body with her younger sister and a girl from their hometown as well as several students from the Austrian town in which the school was to be located. When the school opens, its first group of pupils includes the two English girls and six more from local families. The Austrian girls demonstrated familiarity with the conventions of British school stories, as all of the girls wondered who might be named Head Girl. “’Ah yes; I have read of the Head Girl in your English school-stories,’ replied Gisela pleasantly. ’And also Prefects’.”[5] Through their reading they were quite clear what school would be like.

The first days depicted in Eleanor Brent-Dyer’s The School at the Chalet are not only the first days for new pupils, but also for the school itself. Madge Bettany founds the school and populates the student body with her younger sister and a girl from their hometown as well as several students from the Austrian town in which the school was to be located. When the school opens, its first group of pupils includes the two English girls and six more from local families. The Austrian girls demonstrated familiarity with the conventions of British school stories, as all of the girls wondered who might be named Head Girl. “’Ah yes; I have read of the Head Girl in your English school-stories,’ replied Gisela pleasantly. ’And also Prefects’.”[5] Through their reading they were quite clear what school would be like.

[1] Nancy G. Rosoff and Stephanie Spencer, “‘I keep wondering what school will be like’: The Depiction of Early Schooldays in British and American School Stories,” Sixth Biennial Conference, Society for the History of Children and Youth, New York, NY, June 2011.

[2] Dorita Fairlie Bruce, Dimsie Goes to School (London: Oxford University Press, 1932), 2 [this edition is part of an omnibus collection of the first three books in this series; the original Dimsie Goes to School was published in 1921 as The Senior Prefect, with the title changed to Dimsie Goes to School in 1925].

[3] Pauline Lester, Marjorie Dean High School Freshman (New York: A.L. Burt, 1917), 19.

[4] Ibid., 44.

[5] Elinor M Brent-Dyer, The School at the Chalet ( London: Chambers, 3rd reprint 1937, fp 1925), 60.

Dimsie’s missing mother. In the American stories, parents may play a larger role, since the schoolgirls live at home. American parents frequently host lavish parties and often serve as moral beacons for their daughters. For example, we learn that, in a moment of crisis, “Grace had thought of consulting her mother, her best and wisest counselor at times, but Mr. and Mrs. Harlowe had gone on a long drive to the home of Mrs. Harlowe’s mother … “ (Jessie Graham Flower, Grace Harlowe’s Plebe Year at High School (1910), 103). The absence of Grace’s mother forces Grace to think through the proper course of action to undertake to rescue her friend Anne, who had been kidnapped by her father, an itinerant actor. The contrast made between the steadiness of Grace’s parents, who function as a moral compass, and the untrustworthiness of Anne’s father, who is constantly on the move and demanding money from Anne (who has none to spare), allows the reader to understand what sort of conduct separates right from wrong.

Dimsie’s missing mother. In the American stories, parents may play a larger role, since the schoolgirls live at home. American parents frequently host lavish parties and often serve as moral beacons for their daughters. For example, we learn that, in a moment of crisis, “Grace had thought of consulting her mother, her best and wisest counselor at times, but Mr. and Mrs. Harlowe had gone on a long drive to the home of Mrs. Harlowe’s mother … “ (Jessie Graham Flower, Grace Harlowe’s Plebe Year at High School (1910), 103). The absence of Grace’s mother forces Grace to think through the proper course of action to undertake to rescue her friend Anne, who had been kidnapped by her father, an itinerant actor. The contrast made between the steadiness of Grace’s parents, who function as a moral compass, and the untrustworthiness of Anne’s father, who is constantly on the move and demanding money from Anne (who has none to spare), allows the reader to understand what sort of conduct separates right from wrong.